CASE STUDY

Writing Translations for Genealogy: A French Baptism

Uncover your ancestry with the expertise of Backlog's complete French genealogical record translations - bridging the language gap and bringing your family history to life

Background

Nicolas Maréchal/Marchal may have died in St. Louis, Missouri, but like many other early St. Louisans, he was born in France. As fate would have it, they write French records in France, which leaves their distant American cousins scrambling for either language lessons or a translator. If feeling ambitious, you might create your own translations, if not, we’ve got you covered.

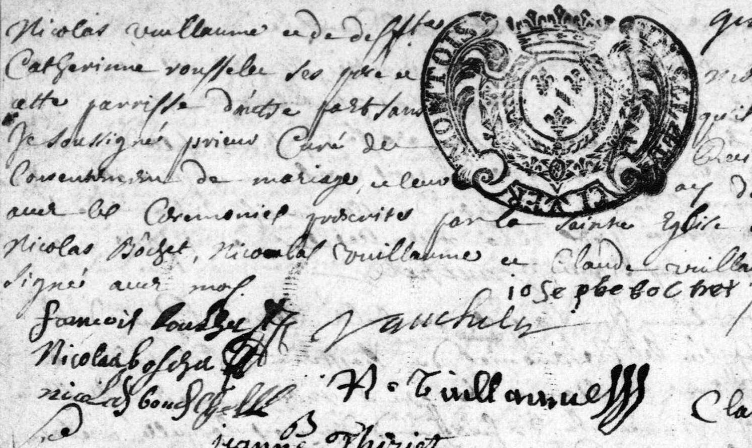

Figure 1.

Methods

Backlog’s genealogists have years of experience reading and translating handwritten text. The translations include a transcription of the original text, a listing of personal and place names, and explanatory footnotes where appropriate. A link to the image within the digitized collection is provided, if available, beneath the title of the document for quick and convenient access.

Nicolas Marchal Baptism, Saint-Vincent de Récicourt, Verdun Diocese,

Meuse Département, 16 Aug 1709 im132, Translation by Jennifer Rigsby

Results

In the Nicolas Marchal example (Fig. 1), the title of the document cites the collection in which the record is found, including church name, diocese, département, and page and digital image numbers (1). When possible, a link to the image within its digitized collection is located directly beneath the title, which provides quick, convenient access to the entire church book. In France, records are available on websites hosted at the département level and are then further divided by parish. Outside of large cities that contain many parishes, the name of the town is usually enough to locate the parish.

Preceding the translation are alphabetical lists of the names of people and places mentioned in the record. In this case, there are two people named Nicolas Marchal mentioned in the baptism record, so “godfather” is written in parentheses to distinguish them. The priest is likewise listed with a parenthetical note to help separate his name from friends and family.

A list of geographical names follows the personal names. In this example, Nicolas was born in the commune of Récicourt, which is in the arrondissement of Verdun, which is itself in the Meuse département of the Grand Est région. Although there are no exact equivalents in the U.S., these might be thought of as the town, district (or group of towns), county or state, and a larger region composed of multiple départements. In this case, the place of baptism is the only relevant place, but marriage records may reference several places. I start the place name with the country instead of the town to keep the list sorted by the place when multiple countries are mentioned in a record.

To capture the original record in translation, verbatim translations are ideal for research purposes. In verbatim translations, like the one we used in the Nicolas Marchal example, the translator takes a more literal approach to preserve original punctuation, capitalization, and even run-on sentences; they won’t attempt to dress up the text with modern expressions or action verbs.

Despite attempts to stay close to the original, not all idiosyncrasies in text lend themselves to translation. For example, the last two words of the baptism read “avec moy,” or “with me.” Moy is an archaic spelling of the better-known moi, but there is no reasonable way to represent this in the English “me.” Because it’s not possible to relay most spelling variations through translation, our genealogist chose to always use the correct spelling to be consistent.

The translation is followed by a transcription of the original text as seen in the record image (Fig. 2). Our genealogists indicate guesses at words or names as well as editorial notes and insertions with italicized brackets like [this]. Illegible words and names are similarly noted in brackets [? 1 word].

Various names of relatives and other associates appear in church records, but it is difficult to read unknown names, particularly when the names belong to another culture. While deciphering the names of godparents and witnesses can be tricky, in many cases we can figure out the name by looking at other records in the town. Even a quick look into the town’s history can sometimes clarify the names in a record. We always spend at least a few minutes doing this not only because it can be a simple way to improve a translation, but also because the people an ancestor knew can provide big clues.

There is often more to know about a record than what the text tells us on the surface. Backlog uses footnotes to relay extra information about records we translate. This could include information on translation choices, explanations of non-standard processes, or even a bit of history on the priest. While the baptism of Nicolas is standard, Récicourt had once been known by other names, which we opted to point out in the second footnote.

Conclusion:

Translating key genealogical records can be challenging, especially when the names belong to another culture. Backlog provides complete translations to make the process easier for researchers. To achieve the best results, it is recommended to come up with a format that works best for you and to decide on the translation rules to follow. For more information on finding and translating records in other languages, email hello@backlog-archivists.org.

(1) Nicolas Marchal baptism, Saint-Vincent de Récicourt, Verdun Diocese, Meuse Département, 16 Aug 1709 im132: https://archives.meuse.fr/ark:/52669/a011500569439yx5R8S/9820525f89