CASE STUDY

St. Louis Property Research

Land records for Missouri are some of the most available historical records. Not only do they reveal much about early Missouri history (1), broadly, but they can also offer answers to questions you might have about the history of a piece or pieces of land, specifically. Backlog recently tackled one such question for a client who wished to learn more about the history of property located in present-day St. Louis County.

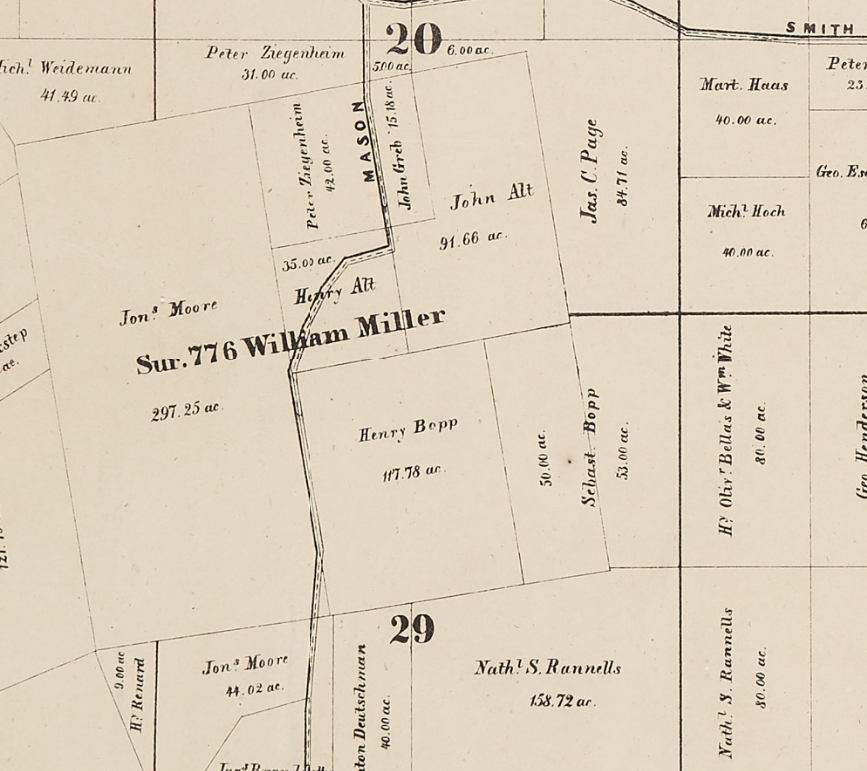

The property of interest was part of a Spanish Land Grant to William Miller in 1799, located in Survey Number 776, Township 45 North, Range 5 East. The client provided a map dated 1862 showing this area and the current landowners at that time, along with the boundaries and acreages of their properties. The question was: who owned the land between 1799 and 1862? We were asked to research the historical ownership of eight tracts that, according to the map, belonged to six individuals in 1862: Henry Alt, John Alt, Henry Bopp, Sebastian Bopp, John Greb, and Peter Ziegenhein.

Our Search

Although the land in question is located in what today is St. Louis County, we knew the records we were looking for would be found in St. Louis City archives. This is because records created prior to the 1876 separation of the City of St. Louis from St. Louis County are housed in City government offices. With this in mind, we conducted our research in the Recorder of Deeds Archives Department at City Hall in downtown St. Louis.

St. Louis City Hall

From there, we began with what we knew: the names of the people who owned particular tracts of land in 1862. Tracing property ownership from these individuals back to the turn of the 19th century required a combination of methods due to the ways in which deeds have been indexed over time.

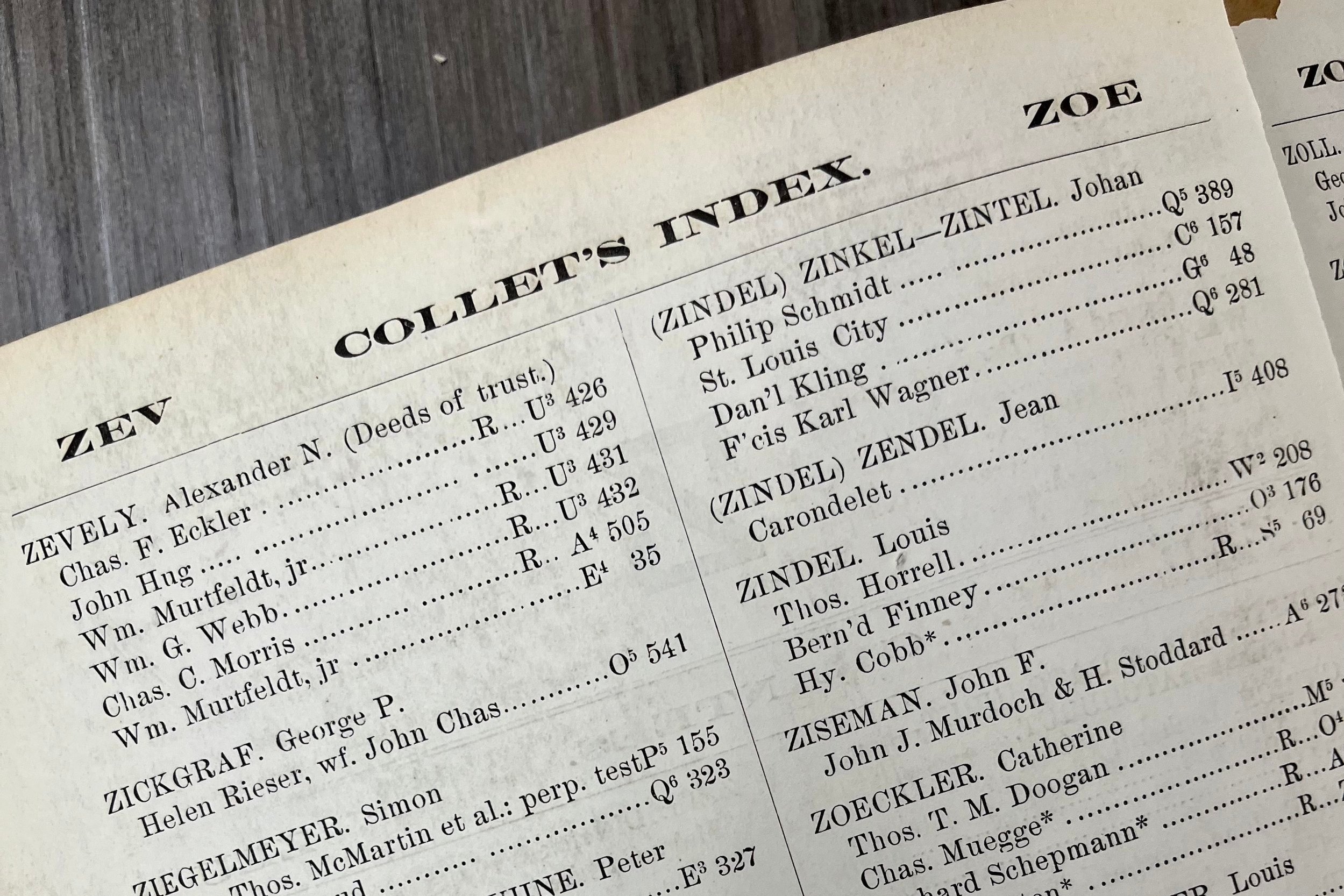

First, we consulted Collett’s Index, a multi-volume index of early St. Louis deeds by both grantor and grantee, which is housed in the Recorder of Deeds Archives Department. Collett’s Index, however, only includes entries through the early 1850s, meaning that transfers of property that occurred after around 1850 would not be found in these volumes. Thus, we also needed to rely on Recorder of Deeds Indexes, which are available on microfilm. These indexes are organized by the first letter of the surname, and the entries are arranged chronologically by year. However, the names are not in alphabetical order, and so researchers sometimes must peruse dozens, even hundreds, of pages to find the correct entry, depending upon how much information is known. Both of these indexes list the Deed Book in which the land transaction was recorded, along with the page number. Deed Books are also available on microfilm.

Collet’s Index

Once we found the names of owners in either of the indexes, we could use the information therein to find records in the appropriate Deed Book. Because individuals often engaged in multiple land transactions with different people over time, not all of the entries in the indexes would turn out to be pertinent to our research. Sometimes, dates and names offered context clues as to whether an entry might lead to the deed we were looking for. Other times, we were unsure, but still needed to check the record, in order to determine whether it described a relevant transaction. And occasionally, a deed referred not only to the recorded transfer but also to the people involved in prior transfers, which helped us know who to look for in additional records.

Our Findings

At the client’s request, we began our research with a particular individual, who owned two tracts of land as of 1862. First, we looked in the grantee volume of Collett’s Index under their surname. There, we found an entry that listed a transfer and the Deed Book in which it could be found. We also looked in the Recorder of Deeds Index for additional transactions. Working backward from the year 1862, we located an entry for a deed that was recorded in 1854. Like Collett’s Index, it gave the Deed Book and page number on which the record would be found.

We located these two deeds and read them closely to determine whether they referred to the property in question, relying on information from the 1862 map, such as the number of acres owned, as well as the location descriptions. In both cases, the information in the deeds matched what we knew. We noted the names of the people from whom this individual obtained the land and repeated the same process to continue tracing transactions back in time.

Once we had determined a chain of ownership for the tracts belonging to one person, we then repeated this process for each of the other five owners and their specific tracts of land. Sometimes, we ran into roadblocks, such as illegible records or information not being where we thought it would be; in such cases, conjecture based on context or finding corroborating information from other records helped us to connect the dots. In addition, the further we went back in time, it became clear that a select number of individuals owned larger tracts of the land that was subsequently divided into the properties shown on the 1862 map. Knowing their names, and having a sense of the dates associated with their ownership, helped in locating the deeds more efficiently than in some of the earlier searches, in which we were less certain about what we were looking for.

One of the property record we found on microfilm.

All in all, the research was like piecing together a puzzle that revealed the story of the land in question through its many owners over time.

(1) European settlers established claims to land in what would become the state of Missouri, including lands inhabited by indigenous populations who were subsequently displaced and/or whose existence was, and often continues to be, diminished or denied, whether through direct, structural, or cultural violence.

(2)Popular genealogical organization and website FamilySearch has a useful list of definitions of common terms found in land records, including concepts like quit claim deed, indenture, deed of trust, and the rectangular survey system that were used in documents over the course of this research.